I believe that there is nothing more significant and valuable in terms of evaluating your well-being than your subjective sense of how you are in any given moment.

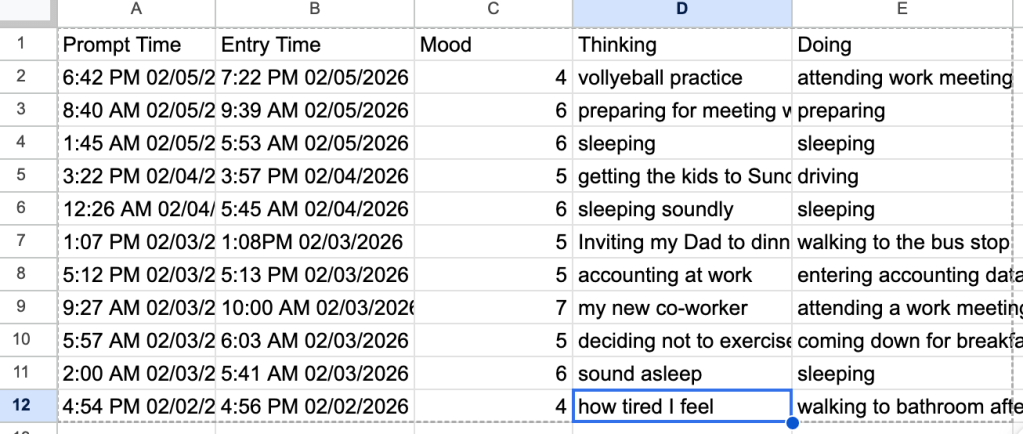

I found it interesting to sample these moments at random and keep a log. I came up with a useful 0-10 mood scale. And, after 30 days of twice-daily random prompts, I looked at the data on a spreadsheet and gained some insight into my mood and the bigger picture. I was interested in my average mood over time, and how different activities, thoughts, and times of day were linked to mood fluctuations.

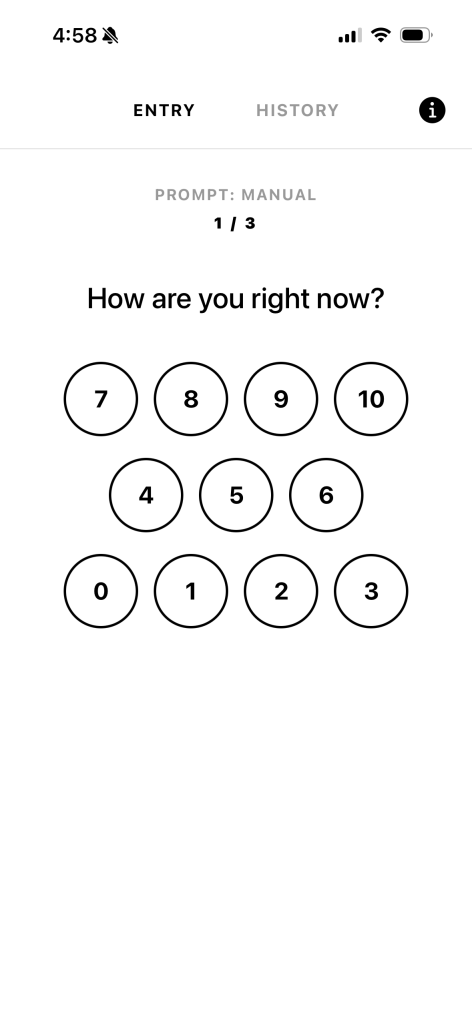

And now, I’ve made an iphone app that makes it easy for anyone with an iphone to do this.

The app prompts you twice a day to rate your mood, and enter a little info about your thoughts and activity. It keeps all the data local on your phone, so there’s no information going anywhere else. And when you are ready, you just tap “export spreadsheet” and you get all your data organized in a .csv file that can be opened in excel, or google sheets, etc.

I wanted to call it Mood Sampler but Apple says someone is using that name. (-Not that I can find any evidence of that!) So, I named it Murray Mood Sampler. I might change the name to Random Mood Sampler, if I can. Regardless, check it out! -Learn about your moods.