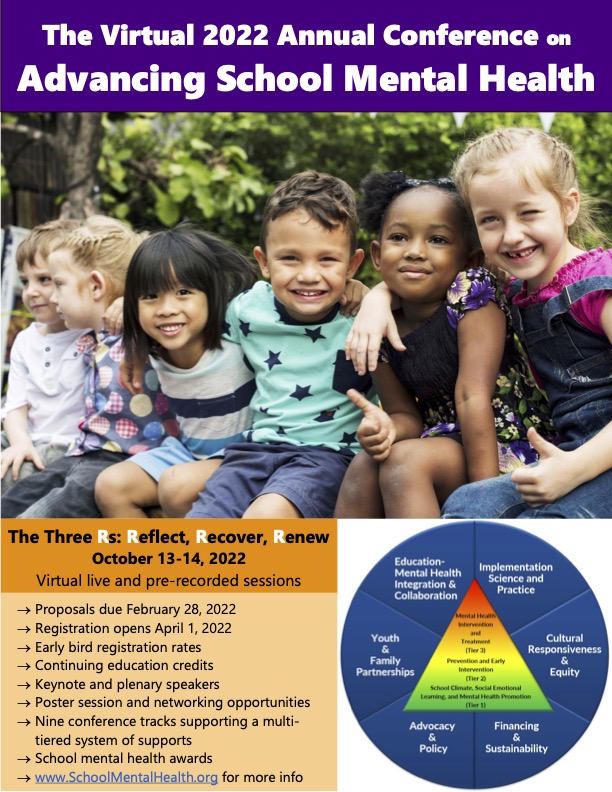

-A little preview of my presentation with Laura Balogh on the therapeutic inclusion program at the 2022 Annual Conference for Advancing School Mental Health at The University of Maryland School of Medicine, October 13th and 14th

Author: murrayof

My book with Laura Balogh is now available for pre-order

Laura and I submitted our proposals to publishers in summer 2021, and signed a contract with Routledge in fall 2021. We really enjoyed writing the book and the process moved right along, and now The Therapeutic Inclusion Program is available for pre-order on Amazon!

The book describes a model for therapeutic inclusion programming in K-12 public schools. There’s more details available about it on Amazon, and other bookseller sites.

Annual Conference on Advancing School Mental Health

My co-writer and I will be presenting at the Annual Conference on Advancing School Mental Health, taking place October 13th and 14th, 2022. The conference will be in virtual format, and is hosted by the University of Maryland School of Medicine. We will be sharing about the therapeutic inclusion model for public schools that we describe in our forthcoming book. https://www.schoolmentalhealth.org/Annual-Conference/

Update

I wrote the following entries in 2018 as I was beginning in private practice, in order to give people an idea of my style. I started with a focus on parent support, but have since expanded to a few other areas of specialization.

Helicopters on the Free-range

One tension in parenting today pits the rustic dream of free-range parenting against anxious times and urban lives. We dream of our children running free through the fields, but in reality most of us have small, fenced-in backyards. We chose our living situations for many reasons that enrich our children’s lives. However, our young ones running through the neighborhood every afternoon from school’s-out to sundown is not in the cards for most of us.

Fortunately, we can still provide our children with opportunities to take appropriate risks, to both succeed and fail with their own wit and grit. Living in a densely populated community, our children are accustomed to having a caretaker or parent nearby to help. It becomes second-nature for the child to call out for help, in the incredibly diverse ways that children draw their parent’s attention. And, asking for help is a strength, most of the time.

In urban environments, we can’t rely on our lack of proximity to support our child’s development of grit, healthy autonomy, and capacity to manage social ties with peers. However, we can develop confidence as parents in knowing when our help is needed, when to intervene, and when to preserve room for our children to build their own problem solving abilities.